This week’s Staff Pick premiere, “Runon” from director Daniel Newell Kaufman, captures the tension of a mother and child in limbo. The film, which debuted at this year’s SXSW, takes its viewer into a grimy, fluorescent-lit bus station where the two eagerly wait. The longer they kill time, the more a nervous energy begins to brim to the surface.

Cinematographer Adam Newport-Berra (“Euphoria,” “The Last Black Man in San Francisco”) uses a single shot for the entirety of the film, placing the viewer in the perspective of the child. Each moment is filled with heightened stimulation, communicating a child-like feeling of confusion mixed with wonder. We at Vimeo were especially taken by the visceral grit that “Runon” conveys.

In honor of today’s exclusive premiere, we got in touch to learn more about the film’s origins. Here’s what director Daniel Newell Kaufman had to say.

On pulling from personal experience:

“I spent way too much time on greyhound buses in my 20s. They were the only way I could afford to travel for a long time. I’ve always connected with the world they reflect. A slice of humanity connected by transience. The film emerged as an exploration of this world —filtered though my family’s own nomadic mythos. My stepfather had just died when I wrote it, and I went to stay with my mother. We were living under the same roof the first time in years. I found myself thinking a lot about the bond and conflict of intergenerational trauma, and the drive to escape not only your circumstances but your very self.”

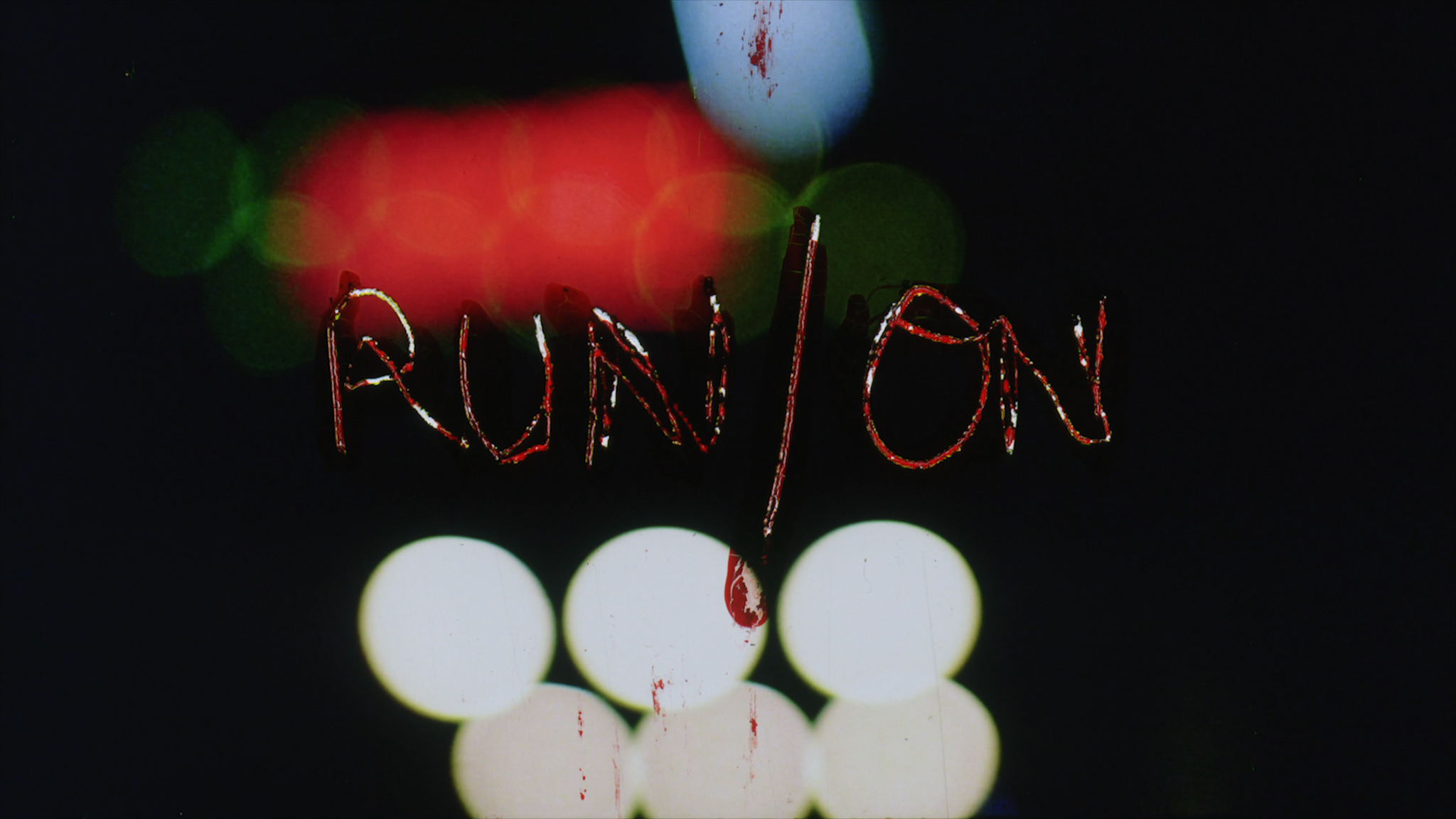

On creating cohesive title design:

“I worked with Joe Ridout of Ana Projects and Cinelab London. We printed sections of the film to new negatives and then scratching on them and scanning them back to digital. Both Joe and I are big Stan Brakhage fans. We’ve drawn from his work on a few commercial collaborations. But I really wanted to take that technique to a new level in terms of its union with story and the emotional core of the film. Here it wasn’t just about a flashy aesthetic trick, but rather about treating the title like a cinematic equivalent of ‘Harold and the Purple Crayon,’ the kid’s book where the line a child scribbles carries you forward through the pages. Only here it was across the frames.”

On financing your own projects:

“The biggest challenge is the same that anyone making a short film faces: getting it off the ground. I tried several routes to get it funded, but realized if I waited around for permission it’d never happen. I kept thinking about Cassavetes putting all the money from his acting gigs into his films — or refinancing his house to pay for ‘Faces.’ So I took heed, and funded it using my earnings from a few commercials. It wouldn’t’ve gotten made otherwise.”

On finding your actors in surprising places:

“It sounds implausible but much of it [casting] came about through serendipity. I was half asleep while my girlfriend was watching ‘High Maintenance’ and I happened to glimpse a shot of Erin Markey in a supporting role. I remember saying in my daze, ‘I like her face.’ Only after did I find out she was also an incredible performance artist and writer in her own right.

I met Luke even more by chance. I was eating Thai food in upstate New York and he happened to walk in with his family and sit at the table next to me. My girlfriend always says I get a certain look in my eyes when I’m about to street cast someone. Luckily Luke’s parents were just as open to the idea as he was — which is incredible because he had no acting experience and barely even watched movies or TV. It was interesting working with two actors with such vastly different backgrounds. Erin so consummate and Luke such an amateur.

After two weekends of rehearsals in a barn upstate, their styles really began to integrate. In a sense, Erin was able to lead Luke through the blocking on screen with a bunch of built in cues. Luke just had to listen and follow her lead — which he did very attentively (when he wasn’t pulling pranks on us in rehearsal).”

On making a film with a single shot:

“I actually had a dream about the movie in which I was walking through a bus station. I remember the chairs being red and the fluorescent lights buzzing. Its continuity felt realer than real. When I woke up, it struck me that it felt like my most vivid memories from childhood. I wanted the movie to feel like this: as experiential and kinesthetic as possible. So that Luke’s perspective felt emotionally undeniable. It struck me that as he’s pulled into a cycle of intergenerational trauma that even his mother can’t escape from. We feel like we’re being drawn into this karma loop with him — only escaping when Luke finally breaks free and the first cut happens about ten minutes into the film.”

On attention to detail in a location:

“It was important for the whole film to feel seamless, but we needed a bit more control that the one location could provide us on its own. Emmeline, our production designer, did a great job of complementing and accenting the existing space — focusing in on targeted use of color like the red chairs (surprisingly difficult to get on a shoestring) and specific graffiti and ware in the bathroom. We wanted the space to have a fine balance between naturalism and style — like a memory in which certain details feel super-saturated.”

On the importance of sound:

“I think it was Bresson who said that after you shoot a film, it dies until you assemble it and bring it back to life with sound. I feel that way 100 percent. Rushes feel two dimensional, and sound and sound design brings that third dimension. In this case it was able to further emphasize Luke’s subjectivity — placing you viscerally in his experience. I was also surprised by how much the puzzle of sound design can revive moments that otherwise sag or don’t work. With a one shot, that was a saving grace. I was able to do a lot of writing and tightening and embroidery with sound to make the whole experience feel sharper and more immersive and experiential. It’s actually my favorite part of the process — sort of like composing music.”

On not waiting for permission to create:

“Don’t wait for permission to make anything. Be prolific, and allow yourself to make work that’s bad. It’s how I spend most of my time — but it’s also how I learn. My dad loves something that the Japanese painter Hokusai said. ‘But all I have done before the the age of 70 is not worth bothering with. When I am 80 you will see real progress.’”

On developing “Runon” into a feature:

“I’m currently shooting a documentary about Stone Mountain Memorial in Georgia. When I’m not down filming in the heat of the south, I’m quarantining up north. I’m in development on a feature version of ‘Runon.'”

Check out more Staff Pick Premieres

If you’re interested in our staff picks, you may also want to learn more about how you can use Vimeo before your video gets to the Vimeo video player, you can also leverage Vimeo's editing tools like the clip trimming tool, file combining feature, compression assistant, frame cropping utility, animated GIF tool, and more.